Long before she helped pioneer NASA research or earned the Collier Trophy, Susan Weisenbach Johnson was learning the art of flight alongside her father, designing and flying Free Flight (FF) models in Cleveland. What began as a childhood pastime grew into a lifelong passion that carried her from local fields to NASA’s research labs. Throughout the decades, Susan helped advance aeronautics, mentor future engineers, and champion women and youth in STEM.

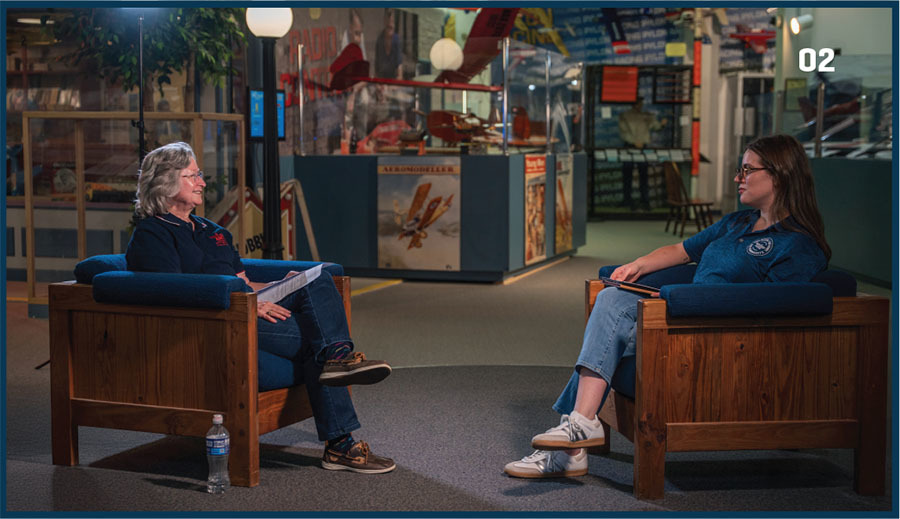

In this conversation, she reflects on her journey through model aviation, engineering, and mentorship—and how those early balsa models helped launch a career that truly soared.

HOLLY SILVERS: In 1970, you were one of the first two recipients of the AMA Scholarship. How did receiving that scholarship aid in your education?

SUSAN WEISENBACH JOHNSON: It aided by actually paying for almost all of my college tuition at the time. Back in the day, college tuition was fairly low. Between that scholarship and a couple that I received from the Cleveland area (where I lived), that pretty much paid for my college for almost all four years. That was a huge help.

It also helped in another way. It wound up validating what I was interested in at the time: engineering. I already knew that I was going to go into engineering; where would I wind up with a job though? At the time, with the competitions I had already won and the scores I got in high school, it proved that AMA trusted me to move on to the next level of my career.

HS: What initially inspired you to get involved in the world of model aviation?

SWJ: Like many other modelers, it’s usually a father, and that’s my case as well. My dad was involved with models even as a high schooler. In fact, I was doing some family research and discovered that my dad had started the model airplane club at his high school and was the president, so I knew he had an early interest. He then continued while he was in the U.S. military for a while. When he got home, he picked up where he left off.

He was involved in flying a lot but also in designing the models. We were all FF at the time. In fact, we pretty much continued that way throughout our family history. In 1957, he designed the Weiser model airplane. He started flying that when we went to the Nats. That design really continued in its evolution of becoming half of a 1/2A FF Weiser and half of an A Gas model design. It evolved to me picking up and flying it. After a while, I was just interested. My dad didn’t want to force any of us into flying, but I just really liked it and took it from there.

HS: In what ways did aeromodeling influence your career at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland?

SWJ:I liked the craftsmanship. Back in that day, it was the Builder-of-the-Model rules, so what you flew, you had to build, and I liked building the models. But then you had to take it to the next step, which was to fly them, and then you had to learn how to trim them. Fortunately, my dad knew how to trim them, but again, I had to build, cover, and dope them. I did all of that.

As I moved through school, I was good in math and science. It wasn’t until about the eighth grade when I took an aptitude test that said, "Well, gee, you’re good in math and science, and you have this great abstract-reasoning, 3D-visualization mind. You should consider engineering." That was the first time I even heard the word, really, and tried to realize that I could put aeronautics and engineering together.

HS:Is there any piece of advice you would give to a young girl who is interested in this in their life?

SWJ: Once I was hired at NASA, I was put on the recruitment path right away to get other young girls and young women involved in the STEM fields. It’s hard to convince them that they can do it. I don’t know why, but I think it just takes a lot of encouragement from others. Even parents, teachers, and guidance counselors can be very critical. It also helps if they can find other opportunities to get exposure to those fields.

For instance, I’m a member of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), and every year we run two STEM activities. I’ve seen more and more girls getting involved in those activities. One of them is Young Astronaut Day, where we challenge school teams of approximately six students to build and collaborate on three or four challenges. We theme it around aeronautics or aerospace, depending on what we decide that year.

We do that and we run a young aerospace visionaries’ competition. This is an individual contest where the theme might be "What would a moon base look like?" or "How can helicopters help society for safety?" It’s up to them to design the vehicle, the application, and then write a paragraph. Those sorts of opportunities are how we try to get girls and other students involved and expose them to the STEM field.

When I graduated from college and got hired by NASA, less than 2% of the engineers and scientists at NASA were women. Now, women make up about 18% to 19% of the scientists and engineers who work at NASA. It’s improved, but it could go higher; however, it’s a step in the right direction of getting students interested.

HS:You mentioned your work with AIAA. STEM is a very important aspect of the hobby. AMA’s Education team really advocates for STEM education, so it’s good to hear that you’re so involved in that.

SWJ: Yes. I had a couple of coworkers, even at NASA, who would run summer camps, and they would want a work unit to build a model airplane or something. I would usually run those building events. At first, I was always a little scared of bringing single-edge razor blades, but the kids did great. I was amazed at the care they took. You give them a safety-first talk, and then you guide them along with building the models.

As I said earlier, as soon as I was hired at NASA, I was put on the recruitment road. I would go to colleges and do a lot of speaking engagements to different groups to talk about engineering and my career and try to inspire others to encourage their children or their high school students to pursue engineering, and that it all works out. There are a lot of different engineering perspectives and opportunities; aeronautics is just one. There are also mechanical engineering and electrical opportunities—so many more now than there were back then. If someone has an interest in engineering and can get through the college courses, the opportunities are there.

HS: Your team at NASA received the Robert J. Collier Trophy in 1987 for the development of advanced turboprop propulsion concepts, which is quite an impressive achievement. What did you learn from that experience, working on a team like that, and winning such a prestigious award?

SWJ: The Collier Trophy? Well, of course, we didn’t know we were even going to win anything at that level at the time. NASA had many projects, and that project was actually one of the first I was on. I was a research engineer initially, and then a project engineer and a project manager, so I was a project manager during the advanced turboprop project that won the Collier Trophy.

There were a lot of people on that team, not just NASA experts and researchers. We also had contractors; we were a huge team. I would say that when I look back on it, we were able to form a team with many competent people, and we had great communication among each other.

Both management-wise or scientific- and engineering-wise, we managed to come up with some new research that had really never been done before. What was interesting about that research is that [Leonardo] da Vinci, back in the day, came up with a similar idea in terms of these scimitar-shaped propellers that helped to create a propulsion system that was going to be extremely fuel efficient. At the time, yes, da Vinci knew about propellers; he had designed and drawn them, but he didn’t have the materials or the machine shops and the expertise to make that sort of idea come true.

There are a lot of us in research, and we have great ideas. We ask, "Are we there yet? How do we get there with the materials or the computing power that we have?"

HS: What was your favorite aspect of working in the aeronautics field?

SWJ: Oh, wow, let’s see. I started in aeronautics research. You think there’s already answers to all of the questions, but we have more questions than we have answers. Even though we think we’ve solved enough questions about propulsion, fuel efficiency, or other barriers to science, there’s still more that we have not figured out yet. That’s the challenge. It’s getting the right question formulated—even knowing how to ask the question to begin with—and then trying to figure out how you can answer it and how you figure it out scientifically and engineering-wise.

Sometimes the science doesn’t want to agree with how you want to go about solving it. That’s why I always made sure that I surrounded myself with the best people. Most of the time, 2/3 of my team members easily were Ph.D.s and they were absolutely experts in their area. I would put all of these teams together to then work toward that goal of figuring out a solution—if there was an answer. Sometimes in research you have a question, and you don’t know whether you’re going to be able to answer it.

HS: Now that you’re retired from your long career at NASA, what role does aviation, both full-scale and modeling, play in your life?

SWJ: Well, I’m retired from NASA, but I loved every minute. I probably could have worked there forever, but it was time to move on. I was retired for a couple of years, and then started working on that bucket list full of all sorts of other things. I have not gone into full-scale aviation or even model airplanes since then. Yes, I’m still the treasurer of my model airplane club (the Northern Ohio Free Flight Association), and we still sponsor at least one or two contests here in Muncie every year, but I picked up doing more work with AIAA within the Young Astronauts program, working the STEM angle with the young visionaries, being a judge for those competitors, and then doing all of the other bucket list items that we have when we retire.

I did that for a couple of years, and then I was asked to be a project manager on contract for a company that’s with Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. I was asked to work on military engines. That’s been close to 2-1/2 years now. I have about another six months on that contract, so we’ll see where that goes.

Part time, I’m still working and I’m back in the project management and engineering side of things. Besides that, I work on my bucket list—travel and do genealogy, things like that.

HS:I have one last question for you. I read that you won at the 1966 Nats with your A1 Towline Glider. Are gliders your favorite model airplanes to fly, or do you have another favorite type?

SWJ: Oh, I love gliders. I was doing a little bit of research, trying to think back on when I was a kid flying, and I used Hand-Launch Gliders (HLGs) for my first event. They were easy to build, easy to break, and easy to build again. I started with HLGs then went to the A1 Towline Gliders. I built a couple of A2s after that.

As I got older, I added some Rubber events like the Coupe d’Hiver, and started flying P-30s, Wakefields, and gas-powered models. I started with 1/2A Gas and B Gas and flew up to C Gas, but the D Gas models were a little too big. I could not fly the Rubber models, especially the Wakefields. When I was younger, it was because I couldn’t pull the rubber motor out far enough and hold on to it and try to wind it myself. I had to be weighted down, or my mom would hold me back.

I was flying Indoor models early too, but the very first event I ever flew was U-Control (Control Line [CL]). They used to have a contest in Cleveland called a Balloon Bust. You could fly whatever CL model you had and they would put balloons on balsa sticks. They would put the sticks on the edge of the circle. Your model, if you were holding it just right, could break the balloons. You had so much time to break so many balloons around the circle. Some of the balloons were different heights too. As a Junior flier, that was one of the first events that I flew. Then I went to FF. But gliders were always my first love.

SOURCES:

NASA Glenn Research Center

Comments

Add new comment