By Mark Frankel

As seen in the April 2004 issue of Model Aviation.

Almost three years ago, Model Aviation launched a series of articles to survey the various forms of aeromodeling. The first was Dave Rees’ study of Free Flight (FF) Scale, followed by Bob Aberle’s article about Radio Control (RC) Electrics. In this third installment I will examine RC Scale, limiting my discussion to fixed-wing, powered models in the United States. Scale helicopters and sailplanes are separate topics that will be covered in future articles.

History: Scale modeling is the process of replicating a life-sized object in a smaller size. The earliest replication of aero vehicles probably dates back to Leonardo da Vinci. Reproducing a man-carrying aircraft is the most fundamental reason to build a model airplane.

By the time brothers Walt and Bill Good “invented” radio control in the late 1930s, Scale aeromodeling was already a well-established art in Free Flight and Control Line (CL) circles (pun intended). Modelers are an innovative breed, and it didn’t take them long to see the possibilities of using radio guidance to control miniature copies of their favorite airplanes.

At first the problems were numerous: radio equipment was enormous and heavy, engine power was limited, and the control system’s unreliability was overwhelming.

The earliest radio-controlled scale designs were typically limited to stable, high-wing monoplanes of the Piper Cub configuration. To ensure airworthiness, the designers often increased dihedral angles, increased tail areas, and moved landing-gear positions to avoid nose-overs. These early scale efforts were little more than large FF models interrupted every now and then by radio commands.

RC models were flown in competition during the 1940s and early 1950s, but there was no separate category for scale. Some adventurous modelers competed with scalelike designs, but they were barely different from Rudderbugs and Smog-Hogs of the era. In 1952 Alex Schneider won the RC event at the Nationals with a modified Cleveland Cub kit.

Compared with RC Scale, CL and FF Scale were far more advanced. World War II fighters and multiengine subjects were common among the CL entries, and complex biplanes of accurate outline were entered in the FF event.

Gradually some kit manufacturers began to experiment with scale subjects for the emerging RC market. Most hedged their bets by making the kits suitable for RC, CL, or FF. Harold (Hal) deBolt’s Live Wire series of kits included the mandatory Piper Cub and an Aeronca Champion. Sterling Models offered a Monocoupe and a Piper Tri-Pacer.

The most prolific manufacturer was Berkeley, which seemed to release a new RC scale model every month. That company was also the most adventurous; it offered some of the earliest low-wing subjects, such as the Ryan Navion.

By 1957 RC Scale had matured enough to become a separate event at the AMA Nationals. The “Radio Control Scale Regulations” covered less than a page in the AMA rule book (Competition Regulations), but a basis for Scale competition was formed. The judging was divided into a static evaluation of the model’s fidelity to the full-scale aircraft and a flying evaluation of the model’s ability to perform a series of mandatory maneuvers.

The Scale event grew slowly in popularity and sophistication until 1962, when something magical happened at the Chicago, Illinois, Nationals. “It was a watershed event; incredible Scale models showed up from all corners of the country,” recalls veteran designer and competitor Jerry Nelson. “They were far more complex than most Scale models of that period, yet they worked!”

Jerry remembers Bob Doell, who won Scale with a huge twin-engine JD-1 (the Navy’s version of the Douglas A-26), Joe Martin who placed second with a twin—the Boeing XB-47D (a turboprop variant of the swept-wing bomber)—and Phil Breitling who took third with yet another twin: a Lockheed P-38 Lightning. “The most incredible thing is that those guys were flying reeds!” said Jerry. He is still in awe of their airmanship.

But as the Scale models were becoming more complex, so were the rules—and that was not a good thing. By 1963 the Scale rules included a 15-pound weight limit, and a short three-maneuver qualification flight was required before the model was submitted for static judging. In addition, the flight plan grew to include six mandatory and five optional maneuvers.

The static judging consisted of actually measuring the model’s airframe to determine its fidelity to scale and assessing the model’s “scale operations,” such as retractable landing gear or functioning flaps. To earn points these features had to be displayed in flight.

According to the 1963 rules, the official score consisted of the flight points multiplied by the sum of the static points, which was then added to the total of the scale operation points. This system resulted in some gigantic numbers and made it possible for certain types of models to dominate the contest scene. The rules were unwieldy, but the quality of the models kept improving.

Then the digital proportional radio arrived, and the state of Scale modeling took its largest step forward. No longer was a modeler limited by the hard overcommands of a reed system; control authority could be exercised smoothly and with coordination. Rudder and aileron could be employed simultaneously to provide realistic turns, or throttle and elevator could be used to achieve precision landings.

In 1967, the weight limit was increased to 20 pounds for multiengine subjects, and the wing loading for those 20-pound monsters could not exceed 35 ounces per square foot. Maximum total engine displacement could not exceed 1.25 cubic inches.

The official score was still determined by multiplying the sum of the static and scale operations points by the flight score, but only the highest-scoring attempt was considered; therefore, only one flight provided the entire flight score.

As some prefabrication entered the hobby in 1970, several provisions were added to the rules to emphasize craftsmanship. Section 24.3.1 stated that “Commercially available prefabricated primary fuselages shall not be allowed.” Section 24.3.2 stated that “the builder and flyer of an R/C Scale model shall be one and the same person. There shall be no team entries.”

The next year, the prefabricated (fiberglass)-fuselage prohibition was eliminated, but the team prohibition remained. A new rule regarding craftsmanship was added which required that the modeler must submit a list of all parts and services he or she purchased from others. The intent was to penalize those entries that were largely the work of others.

In 1973, the Scale rules took a dramatic turn. AMA adopted a proposal by Clark Macomber and Dave Platt to form a new event known as “Sport Scale.” This proposal was intended to simplify Scale judging and attract more modelers to competition.

In accordance with the new rules, the practice of measuring the airframe was eliminated from static judging; instead, models were scored from 10 feet away (which caused the event to become known as “Stand-Off Scale”). Details that were not visible in flight (such as cockpit interiors) were disregarded for static judging, and a 10-maneuver flight plan was instituted for all models. Moreover, the official score was simply the sum of the static score and the average of the two top flight scores (three flights were required).

These rules’ simplicity and uniformity brought a breath of fresh air to Scale competition. The Platt-Macomber format was so successful that it became the basis for most modern Scale competitions in the United States.

Modern Competition: The AMA Nationals originated RC Scale competition, and by the mid-1970s other major Scale events began to evolve. In 1976 Harris Lee and Bert Baker planted the seed of what was to become the US Scale Masters Championships.

This contest—initially called the Western Scale Nationals—was the first major all-Scale event held in the United States. Although it primarily attracted modelers from Southern California, it was a success and became an annual event. By 1980 the Western Scale Nationals grew to become the “US Scale Masters” (a name created by Jerry Ortega, who was an avid golfer and an outstanding modeler).

The first Scale Masters was held at Fountain Valley, California. To generate a national level of participation, a series of regional qualifying contests was used as feeder events for the competition. The concept proved to be enormously successful, growing in modeler participation, spectator attendance, and media coverage every year. To further ensure a national flavor, the Masters is rotated to a new location each year.

The Top Gun Invitational Tournament was born in 1989. Created by Frank Tiano, Top Gun has an entirely different format from that of the AMA Nationals or Scale Masters. Patterned after the Tournament of Champions RC Aerobatics competition, participation is strictly by invitation and cash prizes are awarded to the winners. Team Scale became a prominent part of this competition.

Frank managed to negotiate a long-term agreement with the Palm Beach Polo Club in Wellington, Florida, to provide a high-profile site for the tournament that would assure much press and spectator attention. Successful beyond even Frank’s expectations, Top Gun drew a worldwide audience and Scale modelers eagerly sought a coveted invitation from the Top Gun selection committee. The contest is effective in drawing the general media’s attention. Television and national press have given Top Gun the highest level of visibility of any model-aviation event.

By 2000, Top Gun had clearly outgrown the Palm Beach site, so Frank negotiated an agreement with the Airport Authority at Lakeland Linder Regional Airport in Lakeland, Florida—the field that hosts the Experimental Aircraft Association’s (EAA’s) Sun ’n Fun Fly-In. The first year for Top Gun at Lakeland was 2001, and it was a huge success. This contest will likely continue to grow because of its proximity to Walt Disney World and the EAA event.

A serious Scale competitor’s schedule in today’s environment may include kicking off the season with displaying his or her latest project at the Weak Signals’ RC expo in Toledo, Ohio, in early April, followed by traveling to Top Gun in late April. The AMA Nationals follows in early July, and the Scale Masters usually ends the season in early October.

Throughout this season a participant puts in numerous test flights and maintenance man-hours, but to many it is the most rewarding form of recreation on the planet.

Giants of RC Scale Who Stride the Earth: There are three modelers on the current contest scene whose influence has largely shaped modern Scale competition: Claude McCullough, Dave Platt, and Bob Violett.

Claude McCullough is a true pioneer in RC Scale. In the late 1950s, as Scale competition was evolving and docile high-wing monoplanes were regarded as the only subjects that were stable enough to be trusted with radio equipment, he chose to design more adventurous subjects.

He began with a Druine Turbulent—a French low-wing, home-built aircraft—and competed with it successfully on a single channel. This model preceded the famous Astro-Hog, which is considered the first successful low-wing, multichannel design. In 1960 Claude competed with a Martin AM-1 Mauler, and its level of detail was significantly ahead of any other RC Scale machine.

His design résumé is filled with projects that bring nods of recollection and admiration from the Scale community. The Douglas Skypirate, the Fletcher FU-24, the Yak-18P, and the Morrisey Bravo are a few of the McCullough airplanes that advanced the art of RC Scale.

Claude is also extremely active in the Scale modeling administration and governance. He has served on the AMA Scale Contest Board since 1950 and was designated its chairman in 1955 and 1956. He was elected AMA president in 1957 and elected to the Model Aviation Hall of Fame in 1979. Claude has held an elected or appointed office in the AMA for 55 years, which is an achievement that is unmatched by any other modeler.

Currently he competes in Team Scale with Mike Gretz, flying his WACO S3HD. Claude’s latest project is an ambitious 1⁄4-scale rendition of the Northrop A-17.

Dave Platt has driven the standards of Scale modeling by his stunning examples since the 1960s. Born in England, Dave came to the attention of American modelers in 1966 when he won the British Scale Nationals with a North American T-28B Trojan.

As has Claude McCullough, Dave has chosen unusual subjects, employed an incredible amount of detail, and made everything work reliably. In particular, the T-28 was the first British Nationals winner to use retractable landing gear. It featured a sliding canopy with a detailed interior and an accurately rendered Pratt & Whitney radial engine in the cowl. The model is a masterpiece even by today’s standards. It is indiscernible from a full-scale T-28B in low angled photographs.

In 1967 Dave was hired to build large, flying scale models for the movie Battle of Britain. This project became the breeding ground for much of our advanced scale technique. A true understanding of effective weathering and realistic flying speed were two by-products of his work on this movie.

Dave employed Battle of Britain lessons on his next design—the Douglas SBD Dauntless—and Scale history was made. The Dauntless was dimensionally accurate and it wore a finish that was breathtakingly realistic. Dave created subtle smudges, shading, paint chipping, and dents that made the model look far more authentic than any of its peers.

While producing these works of art, Dave was also thinking about the rules of Scale competition. The Platt-Macomber proposal was the result, and, as I mentioned, it became the basis for modern Scale competition.

Ever the philosopher, Dave authored a set of observations about Scale modeling that rival Murphy’s Law for universal truth. His dicta include “You never finish a scale model; you just stop working on it” and “Given a choice, judges will believe wrong information over right.” (For the price of a few beers, Dave will recite this stuff all night.)

To preserve the tribal knowledge of scale design, Dave has produced the highly informative Black Art video series. The tapes cover virtually every aspect of designing and building a competitive Scale aircraft; the series is worth its weight in gold.

In 2002 Dave won the Designer Scale event at the AMA Nationals with a beautifully executed Aichi D3A1 “Val”: a large, lightly loaded Japanese warbird that suits his flying style perfectly.

Bob Violett is the leading force in Scale jets. He contributed to the development of early ducted-fan technology by designing a McDonnell Douglas A-4 Skyhawk that placed second at the 1978 AMA Nationals in Lake Charles, Louisiana. That was the first time a Scale jet had placed in the top two at the Nationals, and all of Bob’s flight scores exceeded 90 points.

He followed the Skyhawk with a North American F-86 Sabre that won numerous Scale contests in the hands of Terry Nitsch. In the early 1990s Bob introduced turbine power to the Scale contest scene, when Kent Nogy flew a Violett Lockheed T-33 with a JPX propane-fueled engine at Top Gun.

Bob’s designs have matured to the point where five of his new North American F-100 Super Sabres dominated the 2002 Top Gun tournament, and he won the event.

Where does RC Scale go from here? No one knows, but I have some guesses about where we are going with regard to equipment, rules changes, and participation.

• Equipment. Many Scale enthusiasts believe that airframe technology has gone almost as far as it can go. Structures currently range from simple tube and fabric to highly complex composite designs. It is now routine to build a model with more strength and less weight than we ever dreamed possible.

Alignment and precision of fit approaches perfection in many kits, and computer-aided design takes airfoil and fuselage-contour reproduction to a level that would have been unthinkable 10 years ago.

Our powerplants are reliable, powerful, lighter, and becoming more affordable. A current-generation kerosene-burning turbine is roughly half the price of a first-generation propane engine, and the thrust output has doubled.

Radio sophistication and reliability is at an all-time high. The features and flexibility of modern computer radios make guidance a nonissue. Difficult control scenarios such as the swing wings on a Grumman F-14 Tomcat are easily managed with modern radios. Even artificial stability is available with the use of gyros. We now have airspeed sensors that can reduce power when maximum airspeed is approached or, conversely, increase power when a stall is imminent.

However, electric power is an area of rapid innovation. In the mid-1990s advances in battery technology and electric-motor efficiency made a new form of Scale propulsion possible.

Bob Benjamin was one of the first Scale modelers to compete on a national level with electric power. He designed several high-wing civilian models—most notably the Taylorcraft and the Aeronca K that performed well at Top Gun.

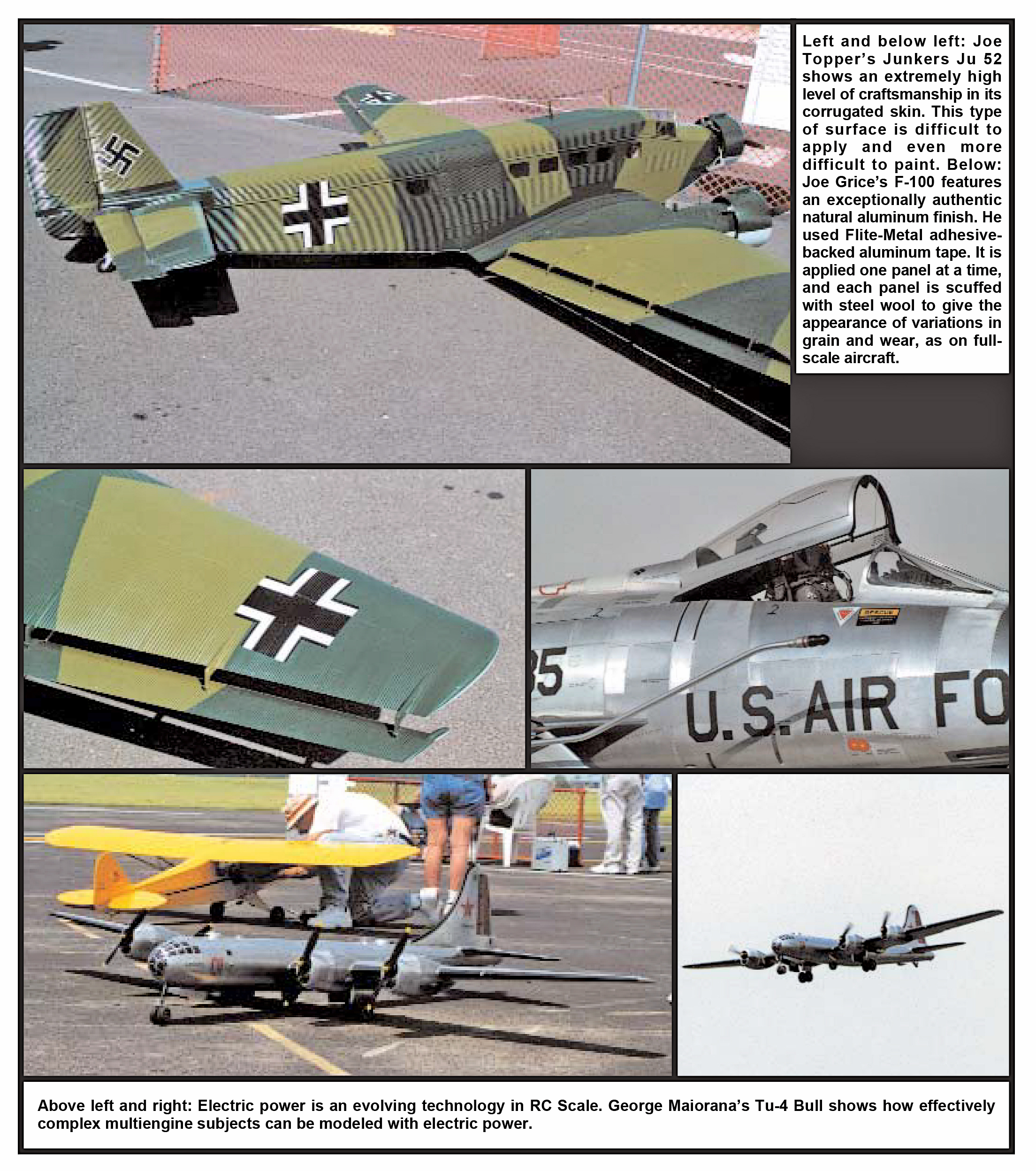

In 1999, George Maiorana showed the potential of electric power by building a large (115-inch-span, 28-pound) four-engine Tupolev Tu-4 bomber. His model demonstrated that electric power is perfect for sophisticated multiengine projects. With electric motors, reliability and synchronization are assured. In the hands of pilot Dave Pinegar, the Tu-4 “Bull” awed the judges at every contest in which it was entered. Electrics will likely continue to be a force in Scale aeromodeling.

There are some “Buck Rogers” concepts on the horizon that may find Scale applications, such as telemetry that provides real-time data for airspeed, altitude, g-force, or fuel state. This could be useful for large, highly loaded models that permit little room for error in flight operations. I suspect that a “caller” would be necessary to read the data and inform the pilot, whose eyes would be focused on the model.

• Rules Changes. The Platt-Macomber concept of Stand-Off Scale has proven to be an excellent framework for competition. There is a good balance between static appearance and flight performance. The quality and quantity of serious Scale models has flourished under these rules, yet there are difficult issues that still need attention.

In regard to craftsmanship, how should the judges deal with high levels of prefabrication? At what point does a highly prefabricated model violate the Builder-of-the-Model Rule?

As far as flying performance is concerned, should jets compete in a separate category from World War I models? How many distinct flight categories should we establish?

In terms of model size, should we maintain a 55-pound limit for competition models, or will this inhibit the development of new projects?

I don’t have the answers to these questions, but the resolutions will mold the nature of RC Scale in the coming years.

• Participation. Many feel that Scale is a dying art—that modelers are uninterested in investing the countless hours of labor required to build a competitive Scale model. However, competition levels show the opposite; Scale participation is at an all-time high. Contestant numbers and spectator attendance at major Scale events are increasing.

The success of Scale ARF (Almost Ready-to-Fly) aircraft has helped bring new modelers into the Scale ranks. AMA has enhanced the trend by providing entry-level competition such as Fun Scale. Furthermore, new forms of Scale competition are beginning to emerge, such as the indoor RC Scale events that Mike Gretz and Ernie Harwood have proposed.

So what is the state of the sport? It has never been better, nor has it ever had a brighter future. The equipment available with which to build an accurate-looking and realistic-flying replica of virtually any man-carrying aircraft is unparalleled. The competitive framework in which we measure a Scale effort’s success is becoming more objective. As I have mentioned, the growth in Scale interest can be seen in the amount of media coverage, the spectator attendance, and the number of entrants at major Scale events.

So if you are intrigued by the idea of building and flying a miniature copy of your favorite airplane, there is no better time to start than now.

SOURCES:

Jet Pilots Organization (JPO)

National Association of Scale Aeromodelers (NASA)

U.S. Scale Masters Association

Facebook

facebook.com/groups/1478836462402358/

Comments

Add new comment